God’s Ax and Noah’s Plank

The Assyrian King Sennacherib was the nemesis of King Hezekiah of Judah. What did he think, and what did he believe? A glimpse into the Bible, History, and Archaeology.

12/12/2012

[Factum 6/2011; translated from German by Walter Pasedag; thanks to Bill Crouse! Online version 12/21/2012, small parts of the translation expanded by Timo Roller]

The siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib clearly shows the harmony between a Biblical account and the events proven by archaeology. But our understanding of the Assyrians is derived from research that has ignored the Biblical story. For example, how does the repentance of the Ninnevites following Jonah’s preaching fit with the understanding of the Mesopotamian pantheon derived from [secular] history?

701 BC King Hezekiah of Judah was trapped in the walls of Jerusalem »like a bird in a cage« (1) - this is the account of his opponent, the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who had besieged the capital with his army and failed unexpectedly. In its annals and the reliefs in his palace at Nineveh there is nothing to read about a defeat: Sennacherib mentions the capture and tribute obligation of Hezekiah. His military victory over the less important city of Lachish is cut into stone. His glorious deeds are recorded for the future generations. The Bible describes very clear how that »bird« was released again:

»That night the angel of the LORD went out and put to death a hundred and eighty-five thousand men in the Assyrian camp. When the people got up the next morning- there were all the dead bodies! So Sennacherib king of Assyria broke camp and withdrew. He returned to Nineveh and stayed there.« (2 Kings 19:35–36)

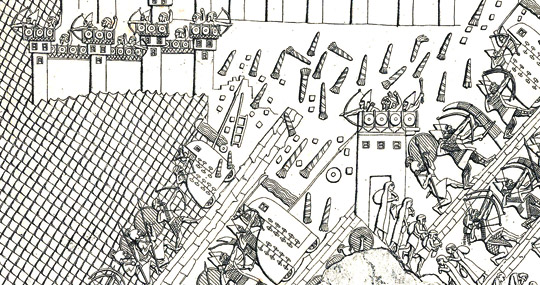

Sennacherib's reliefs were unearthed in 1847 in what is now Iraq. The records show very detailed images of the opposing point of view of the biblical accounts. Known as Sennacherib Prism on a six sided cylinder the Assyrian version of the »Third Campaign« is recorded in cuneiform letters: Hezekiah's imprisonment, the conquest of 46 fortified cities, including Lachish. But nothing about a defeat. No Assyrian ruler would record such messages for his descendants.

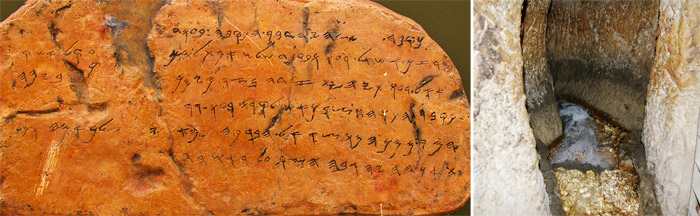

Arrowheads and skeletons that were excavated in Lachish complete the picture of those events. The discovery of the Siloam water tunnel, helping Jerusalem to withstand Sennacherib's siege for a long time, shows the authenticity of the biblical account as well. In 1880, at the southern end of the tunnel there was found an inscription: »And on the day of the tunneling the hewers bore through, one man towards the other, axe upon axe, and the water flowed from the source to the pool« (2).

The »assault on Jerusalem« (3) is a historical event »that like no other in the Old Testament can be proven by archaeological finds« (4).

Even as a young man, Sennacherib was entrusted by his father Sargon II with important tasks, so he was the undisputed heir to the throne when his father died. He assumed the throne, apparently without the usual palace and harem intrigues (5). He was born around 745 B.C., and would have been about 23 when his predecessor Shalmanezer V conquered the Northern Kingdom. Perhaps he was even participating as a young solder?

We can be certain that his father put him in charge of the northern border of the Assyrian empire. Apparently his responsibilities included intelligence gathering, as evidenced by «Messenger reports compiled by Crown Prince Sennacherib and forwarded to the King of Assyria”(6).

When Sennacherib assumed the throne in 704 B.C. he was around 40 years old, approximately the same age as his rival Hezekiah, whose birthday is estimated at 740 B.C. (the dating according the Biblical reigns is difficult because of co-regencies).

Detailed descriptions of eight military campaigns, as well as magnificent reliefs on palace walls demonstrate Sennacherib’s great military successes, as well as his and his countrymen’s cruelty. The impalement and flaying of their enemies are captured in texts and reliefs, presumably to inflict fear and terror in potential rebellious subjects. The prophet Nahum confirms the viciousness of the Assyrians: »Woe to the city of blood, full of lies, full of plunder, never without victims!« (Nahum 3:1).

Sennacherib reinforced Assyria’s position of unchallenged world power. He established a ring of dependent provinces at the empire’s borders, which had to be reinforced regularly with punitive military campaigns. The destruction of Babylon in 689, no doubt, was such a demonstration of military power to reinforcement the supremacy of Assyria in Mesopotamia. There may have been personal grudges involved as well: Sennacherib’s son Assur-nadin-sumi, whom he installed as king of Babylon five years earlier, had been assassinated.

From the secular point of view, the siege of Jerusalem was but a minor episode of Sennacherib’s reign. Not so, however, for readers of the Bible, who get valuable insight into the thinking and religious concepts of the times from the detailed descriptions in 2.Kings 18 -20, Isaiah 36 – 39, and 2.Chronicles 29-32.

The prophet Isaiah was an eye-witness to the onslaught of the Assyrians. Prior to the detailed account of the siege, he provides a glimpse behind the scenes:

»Woe to Assyria, the rod of my anger; the staff in their hands is my fury! Against a godless nation I send him, and against the people of my wrath I command him, to take spoil and seize plunder, and to tread them down like the mire of the streets. But he does not so intend, and his heart does not so think; but it is in his heart to destroy, and to cut off nations not a few« (Isaiah 10:5-7)

God had selected Assyria to execute judgment on apostate Judah! But the greed for power, and the destructive rage of the King of Assyria brought Gods judgment on him as well.

The psychological warfare of the Assyrians was quite impressive. As they stood outside the walls of Jerusalem, a high Assyrian official tries to rile up the population against their king:

»Do you think I have come to attack and destroy this place without word from the Lord? The Lord himself told me to march against this country and destroy it!« (2 Kings 18:25)

At first it seems that the Assyrians do consider themselves to be sent by the LORD, but what they think about God becomes clear with his next sentence:

»No god of any nation or kingdom has been able to deliver his people from my hand or the hand of my predecessors. How much less will your god deliver you from my hand!« (2 Chron. 32:15)

The Assyrians, on the one hand, are not hesitating to use the name of Judah’s God – Yahweh – for the supreme deity, in which they also believe, but, on the other hand, they consider this God as a local deity which is powerless against them. Sennacherib and his top officials are self-confident and arrogant enough to use God for their own purpose, but in the end, their confidence is their own power, as Isaiah states:

»By the strength of my hand I have done this, and by my wisdom, because I have understanding. I removed the boundaries of nations, I plundered their treasures; like a mighty one I subdued their kings« (Isa. 37: 17)

God Himself accuses Sennacherib:

»Does the ax raise itself above the person who swings it, or the saw boast against the one who uses it? As if a rod were to wield the person who lifts it up, or a club brandish the one who is not wood!« (Isa. 10:15)

The apocryphal book of Tobias provides an additional perspective from the time of Sennacherib: Tobias was one of the Israelites deported to Nineveh who upheld their faith in God:

»«A long time later, after the death of Shalmanezer, during the reign of his son [or successor] Sennacherib, who was hated by the Israelites, Tobias comforted the Israelites and distributed his wealth, as much as he could: he fed the hungry, clothed the naked, and buried the dead. But then Sennacherib returned from Judea, from where he had to flee, as God smote him because of his blasphemies. He was very angry about it, hnd had many Israelites killed. It was Tobias who buried them. When the King found out about it , he condemned him to death and confiscated all his possessions. But Tobias fled, with his wife and his son and was able to stay hidden, because he was loved and supported by many.« (Tobias 1:18-23)

A surprising insight into the religious nature of Sennacherib comes from a Jewish tale about what happened on Sennacherib’s way back to Nineveh. The Biblical account has only these sentences:

»So Sennacherib king of Assyria departed, and went and returned, and dwelt at Nineveh.37 And it came to pass, as he was worshipping in the house of Nisroch his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer his sons smote him with the sword: and they escaped into the land of Armenia. And Esarhaddon his son reigned in his stead.« (2 Kings 19:36-37)

Josephus adds: »[Sennacherib’s] own temple, called Araska« (8). The above-mentioned story comes to us through Rabbi Louis Ginzberg (1873-1953), and, presumably, originates from the Mishna tractate »Sanhedrin«.

»On his return to Assyria Sennacherib found a wooden plank, which he venerated like an idol, because it was a part of the Ark that saved Noah from the flood. He vowed that he would sacrifice his two sons if his next venture would be successful. But his sons listened to his vow. They killed their father and fled to Kardu.« (9)

This account, by the way, together with the name »Kardu« in lieu of the Biblical name »Ararat« demonstrates that Mt. Cudi in the south of today’s Turkey is to be preferred as the landing place of the Ark, over the mountain that today bears the name Ararat, since the latter is too far from the route from Jerusalem to Niniveh (10).

In the scholarly literature the term »Nisroch« is connected with an eagle-headed creature, because the words sound similar in Arabic and Persian, and these winged beings play an important role in Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh. »Nisroch« is also connected with Noah’s dove. This may be an attempt to bring the different interpretations into harmony (11).

The fact that the veneration of a sacred object was not unusual practice in those days is illustrated by Hesekiah who destroyed Moses’ staff:

»He removed the high places, and brake the images, and cut down the groves, and brake in pieces the brasen serpent that Moses had made: for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it: and he called it Nehushtan.« (2 Kings 18:4)

The situation with Sennacherib, Hesekiah’s contemporary, appears to be a similar case. In the end, this worship of a relic became his doom, since it caused his sons to conspire against him.

The credibility of this story gets support from Sennacherib’s fifth military campaign, which took him to the north. In 697 BC, the Assyrian army marched to the presumed ark mountain Cudi, where several reliefs carved into the rock testify to Sennacherib’s presence.

As a result of his being stationed in the north during the reign of Sargon II, Sennacherib was very familiar with this region. This is his report:

»My fifth campaign took me to the warriors of Tumurru, Sharum, Ezama, Kibshu Halgidda, Kue and Kana, who wanted to throw off my yoke. Their living places were like eagles nests on the peak of Mt. Nippur a steep mountain. I set my camp at the foot of the mountain, and with my body guards and relentless warriors I stormed up to them like a wild ox. I crossed ravines, river rapids, waterfalls, and steep cliffs in my sedan. When the way became too steep I proceeded on foot. Like a young gazelle I climbed the highest peaks to pursue them. Wherever my knees found a place of rest, I sat on a rock and drank cold water from a canteen. I followed them to the peaks of the mountains and vanquished them. I took their cities and looted them. I destroyed, burned with fire, and devastated them.« (12)

The fact that Mt. Nippur is equal to Mt. Cudi is clear from the inscriptions on the reliefs at the foot of the mountain. Leonard William King (1869 – 1919) documented and translated the inscriptions. They include the account quoted above and include a few additional lines that are preserved only in fragments: He ordered that a relief be carved at the mountain’s summit, in order to immortalize the power of his god Assur. Whoever would destroy it will feel the wrath of Assur and the great gods.

The number of reliefs at the base of Mt. Cudi leads to the conclusion that this mountain had a special significance to the king. Although this campaign appears to have occurred some time after his return from Jerusalem, the acquisition of the relic may have influenced him to take possession of this place.

The cuneiform tablet library of Sennacherib’s successor Assurbanipal (669-627 BC) included a version of the famous Gilgamesh Epic. It gives an account of a king, later deified, who wanted to make a pilgrimage to the Babylonian Noah – Utnapishtim – in order to discover the secret of immortality.

If parts of the ark remained on on Mt. Cudi at that time – and there are several indications suggesting this – then this place, a mere 130 kilometers from Nineveh, must have had great religious significance.

There will always be a certain degree of speculation in the interpretation of events that occurred thousands of years ago. But the Biblical, historical, and archaeological data do not appear to be compatible with the conclusion that the beliefs of the Mesopotamian peoples are completely separate from the Israelite worship of Yahweh. Is the Bible Dictionary really correct when it states that »in most aspects, the Assyrian religion shows little difference from that of the Babylonian, from which it is derived« (13)?

Today many people assume that religion is yet another product of evolution, beginning with primitive ancestor worship, which evolved via polytheism into monotheism. About Assyria it is reported that the god Nabu received a special standing in the eighth century BC: »One could call it monolatry (the exclusive worship of one deity), but it is far from true monotheism« (14). Minimalist scholars, on the other hand, accuse the Israelites of a long-standing polytheism: »We have temple documents from 460-407 BC that show that Diaspora Jews venerated at least three other deities in addition to Jahu, among them Anat, the goddess of love« (15). The belief in one god, according to these scholars, was firmly established only under the Maccabees in the second century BC.

When we consider the Bible to be true, a completely different picture of the development of religion emerges. The belief in the one and only Creator, who later revealed himself to the Isrealites as Yahweh, was there from the beginning. Other gods, who sometimes took the place of God, started to appear later. After [sic] the Flood, people lived very long, in the eyes of their younger progeny they appeared almost immortal (see the Gilgamesh Epic). It is easy to conceptualize that these ancestors were venerated as heroes, saints, and ultimately, gods.

Various scholars, for example, conclude that Nimrod, the mighty hunter, became the Babylonian god Marduk, and, by derivation, Assur (16). In fact, the Mesopotamian pantheon appears to have had a vague remembrance of a creator-god, who had a superior status to Marduk and many other immortals. Over time, God’s place was displaced by Marduk and his cohorts. We should all think about how and where similar displacements are happening today.

The Biblical view of God appears to be affected by three constants: God is eternal, God revealed Himself in the Bible and in His Son, and God chose Israel as His people.

If one of these points is ignored, the resulting understanding of God will be askew. When a created being replaces the Creator, when Scripture is replaced by myths and tales, or when Israel is derided and attacked, we can conclude that we have gone astray.

We should note that Israel and Judah, who heard God’s pending judgment announced to them, and then experienced it, are no different than Assyria, who, following Jonah’s message, changed their view of God, even if only temporarily. And there is no difference for today’s churches, who should continuously test their view of God against the Bible.

What kind of man was Sennacherib? A power hungry, idol worshipping barbarian – or perhaps a seeker? Someone who saw himself carrying out God’s assignment, but anchored his beliefs in the wrong things, and ultimately floundered because of his arrogance?

Sennacherib failed to recognize the God of Israel as his own creator. His view of God no longer corresponded to who God is, and to what Jonah had preached about 75 years earlier, that it is not the ax that is mighty, but He who strikes with it.

It was not a piece of the ark that he should have worshipped, but Him who had the ark built to save mankind. And he hated the Israelites, and was blind to the fact that they were the chosen people. Sennacherib was a prototype of all those religious zealots who are not concerned about God and His will, but arrogantly put their trust in »Holy Men« and inanimate objects, and those who consider God’s chosen people to have been replaced, or worse, to be »Christ-killers.«

Let the 2700 year old words of Isaiah against the arrogance of the King of Assyria be a warning to us. How often do we think like Sennacherib:

»By the strength of my hand I have done this, and by my wisdom, because I have understanding.« (Isaiah 10:13)

Timo Roller

Sources

(1) Sennacherib Prism, see http://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/meso/sennprism3.html

(2) Sign in Jerusalem with English translation

(3) http://www.zdf.de/ZDFmediathek/hauptnavigation/startseite/#/beitrag/video/1300558/Sturm-auf-Jerusalem

(4) Paul Lawrence: »Der große Atlas zur Welt der Bibel« [The Great Atlas of the World of the Bible], Gießen 2007, p. 92

(5) Dietz Otto Edzard: »Geschichte Mesopotamiens«, München 2009, S. 214

(6) Ralf-Bernhard Wartke: »Urartu, das Reich am Ararat«, Mainz 1993, S. 50

(7) Dietz Otto Edzard: »Geschichte Mesopotamiens«, München 2009, S. 214

(8) Flavius Josephus: »Antiquities of the Jews,« X,1,5

(9) Louis Ginzberg: »The Legends of the Jews – Vol. IV«, New York 2005, S. 269f

(10) Timo Roller: »Noahs Berg«, www.noahs-berg.de | English version: www.cudi.info

(11) William Smith: »Dictionary of the Bible«, London 1863, S. 561f

(12) Sennacherib Prism, see http://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/meso/sennprism3.html und http://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/meso/sennprism4.html

(13): Helmut Burkhardt et al.: »Das große Bibellexikon«, Witten 2009, S. 132

(14) Dietz Otto Edzard: »Geschichte Mesopotamiens«, München 2009, S. 201

(15) »Der Spiegel«, Nr. 52/2002, S. 146

(16) David Rohl und Werner Papke, see »factum«, Nr. 7/2010, S. 11f